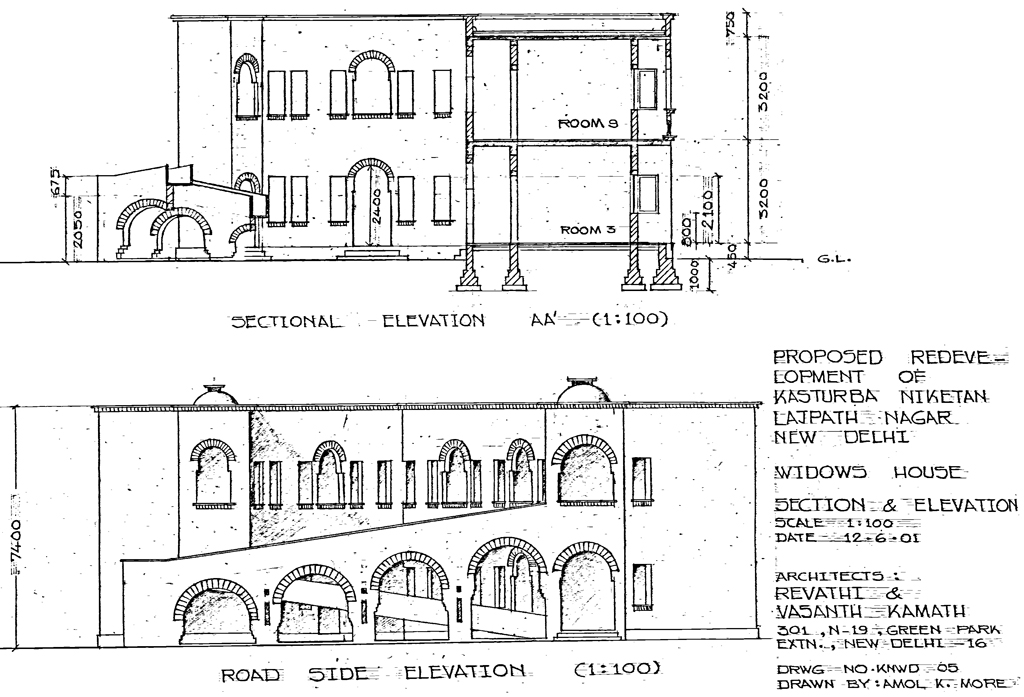

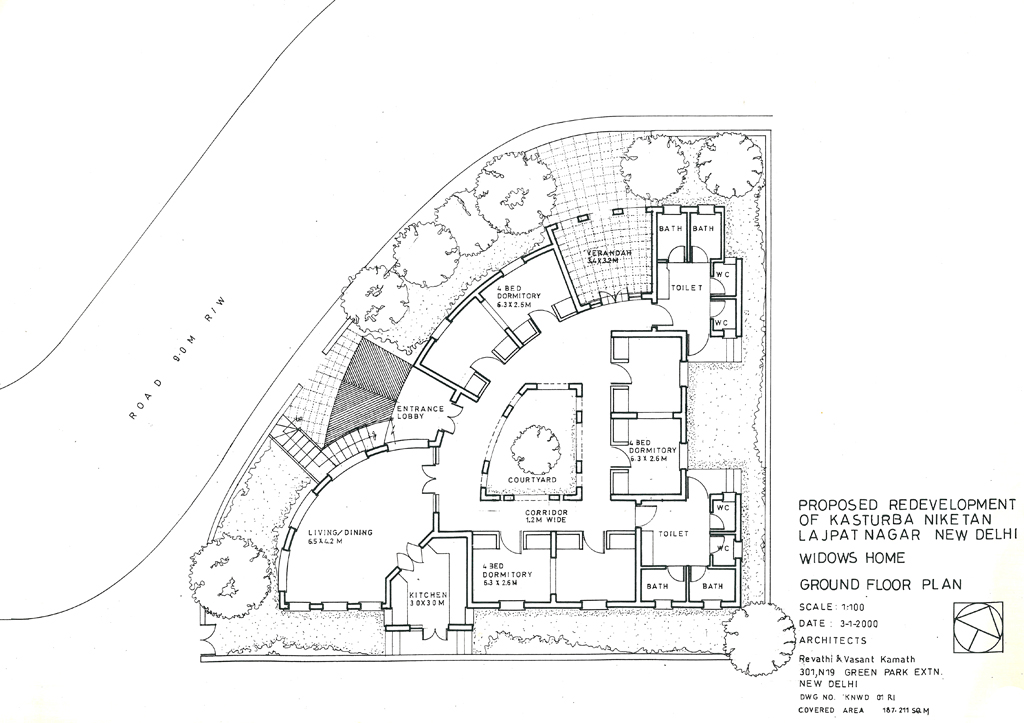

Delhi’s population nearly doubled after India’s partition in 1947. Unlike many families who were allotted plots of land in the city for their rehabilitation, widowed refugees – many with young children- from both East and West Pakistan, were housed in one room barracks on a piece of land in Lajpat Nagar named Kasturba Niketan. From the 1950s various institutions such as the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); the National Institute of the Hearing Handicapped (NIHH), a juvenile remand home and an old age home have been set up on this land. After the 1971 war many Bengali widows were also settled in Kasturba Niketan in dormitories.

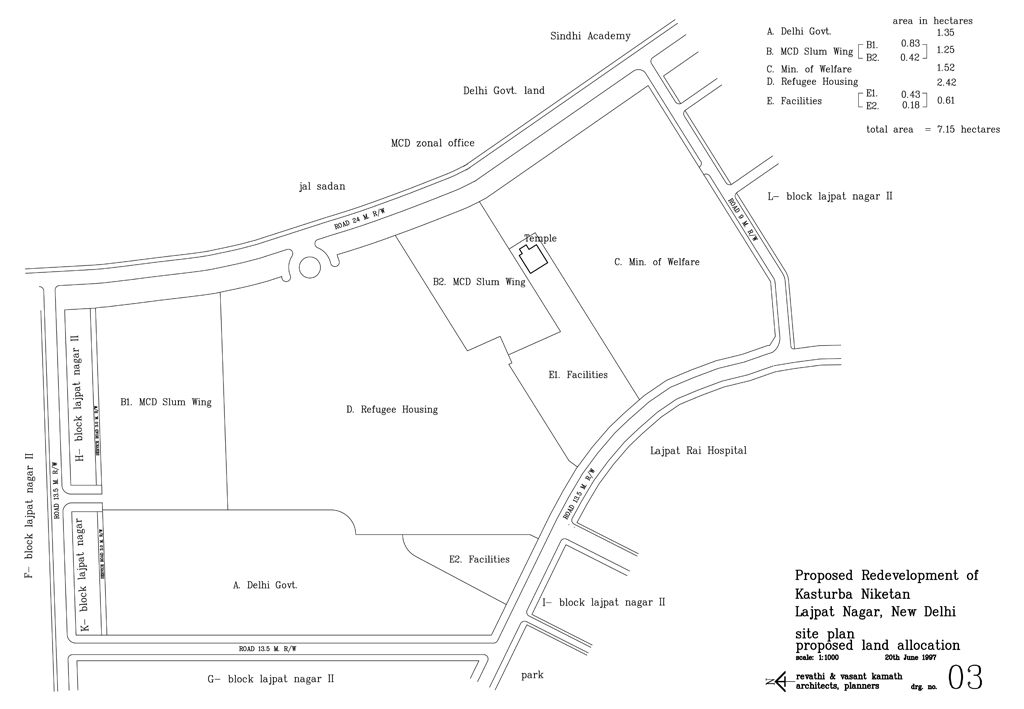

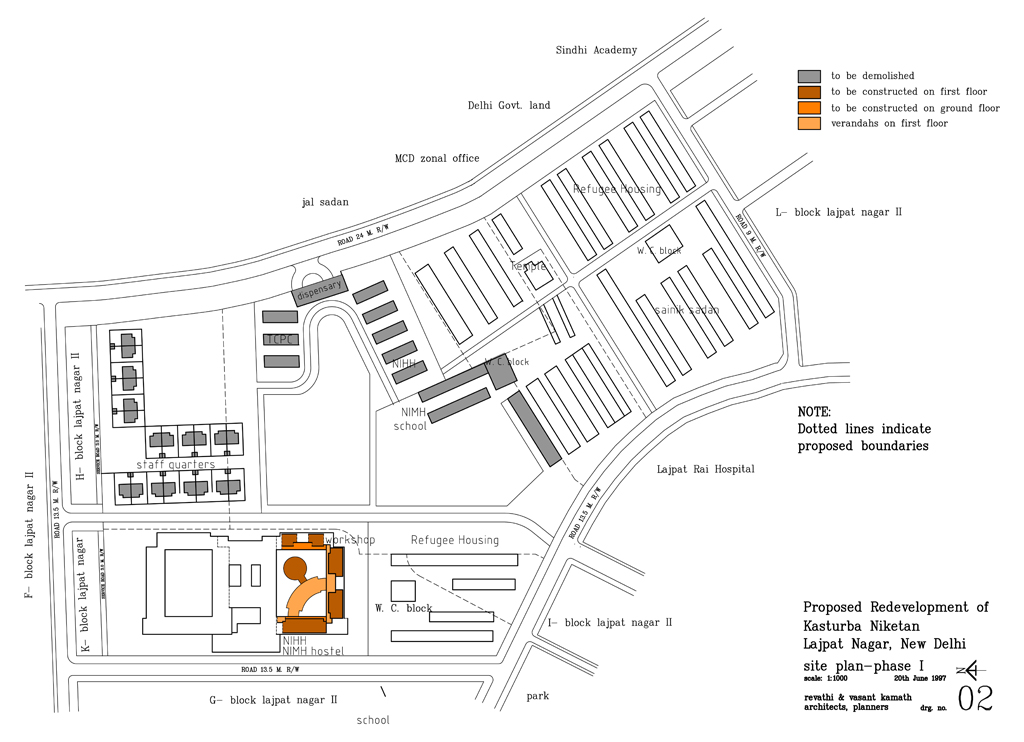

Growing up in Delhi, children of the refugee widows had no secure land tenure and no houses for their families to grow. There was a demand from these families for land to build their own homes. In 1999-2000, the government decided to rehouse these families on plots of land within Kasturba Niketan. Kamath Design Studio was appointed as consultant for the project which was to be executed by the then Slum and JJ Wing of the DDA.

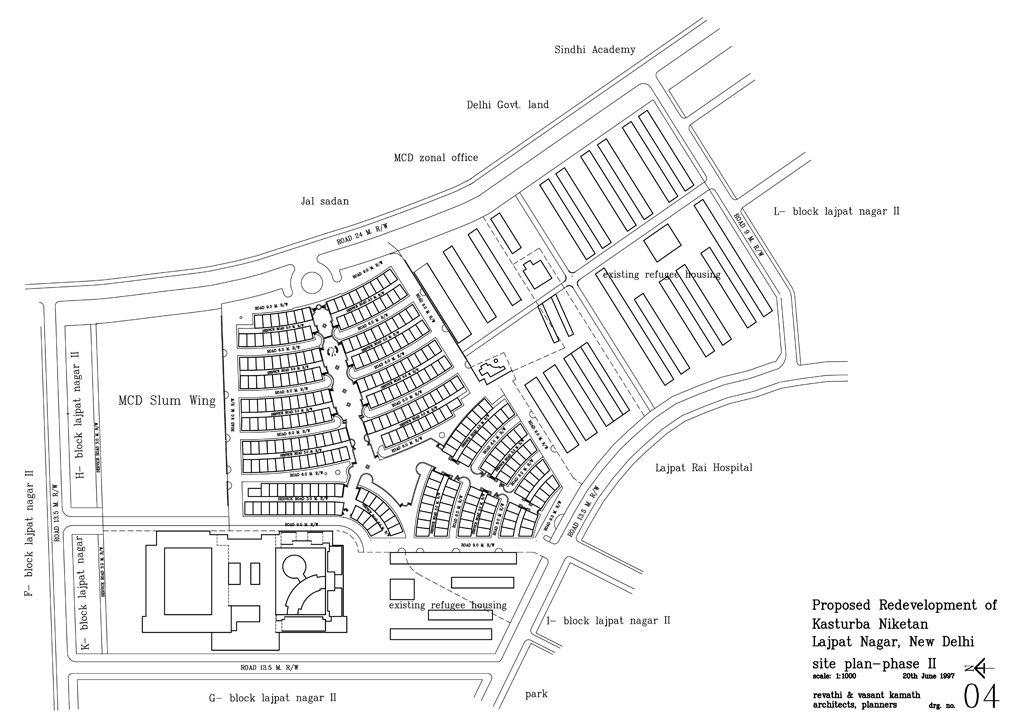

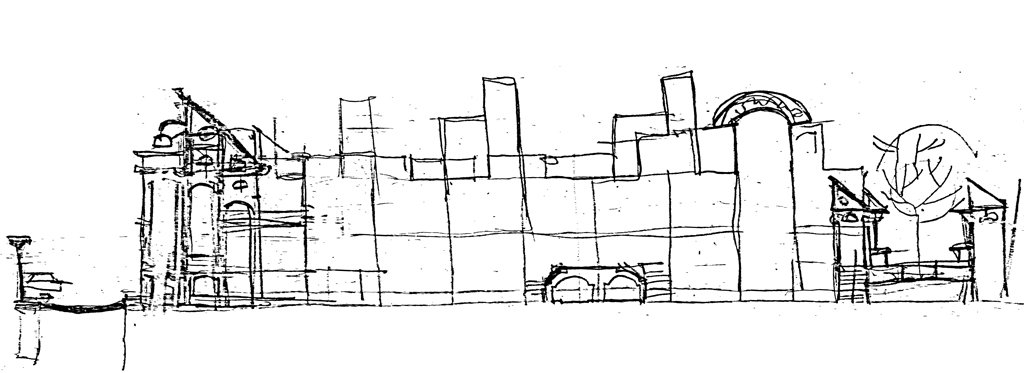

The design challenge was to locate and phase the project such that the one room barracks and dormitories would not need to be demolished while the sites and services of the residential plots were developed to avoid undue hardship to the refugee families. The subsequent demolition of the barracks would free land for the redevelopment of existing institutions on the site and to build new ones.

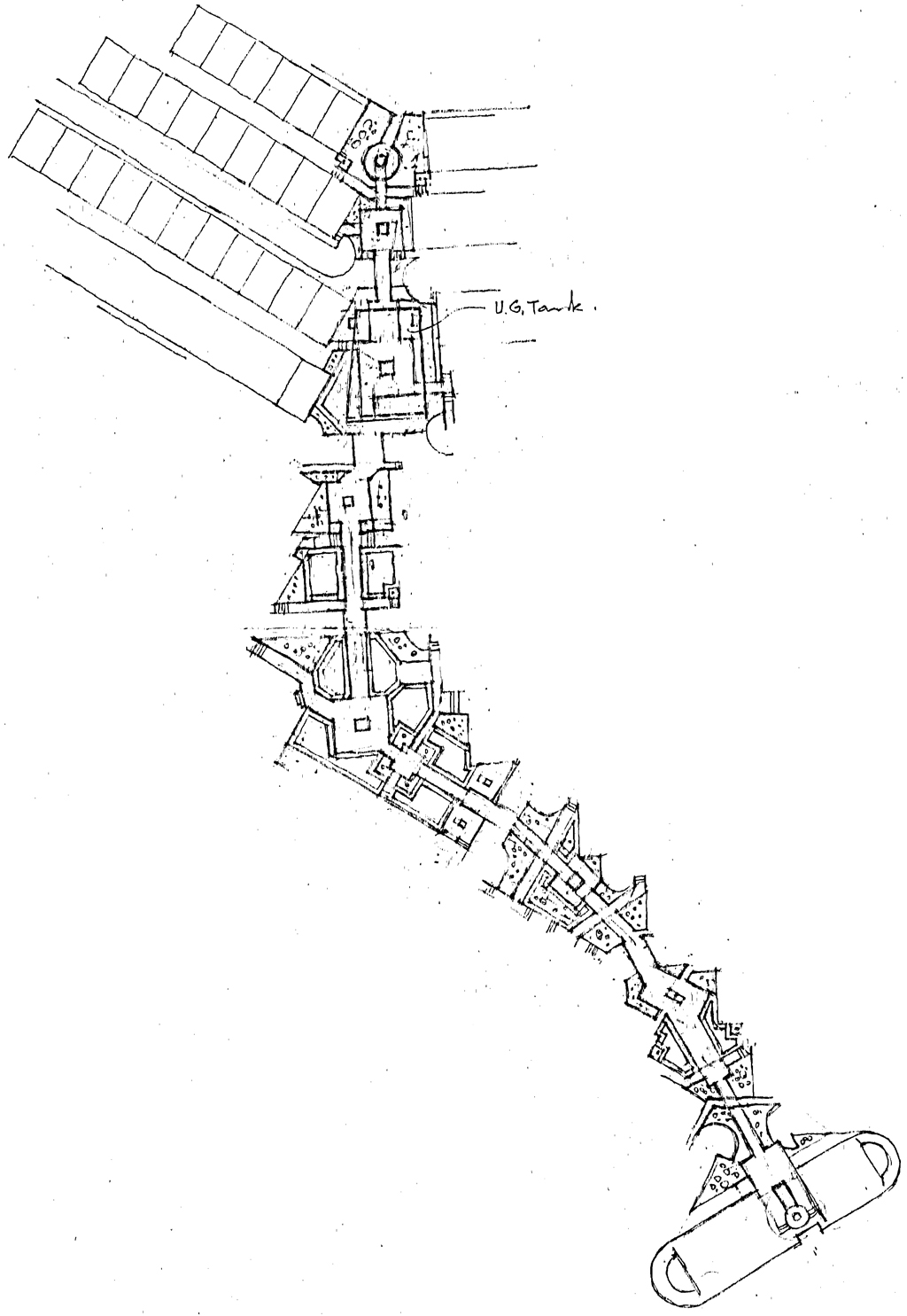

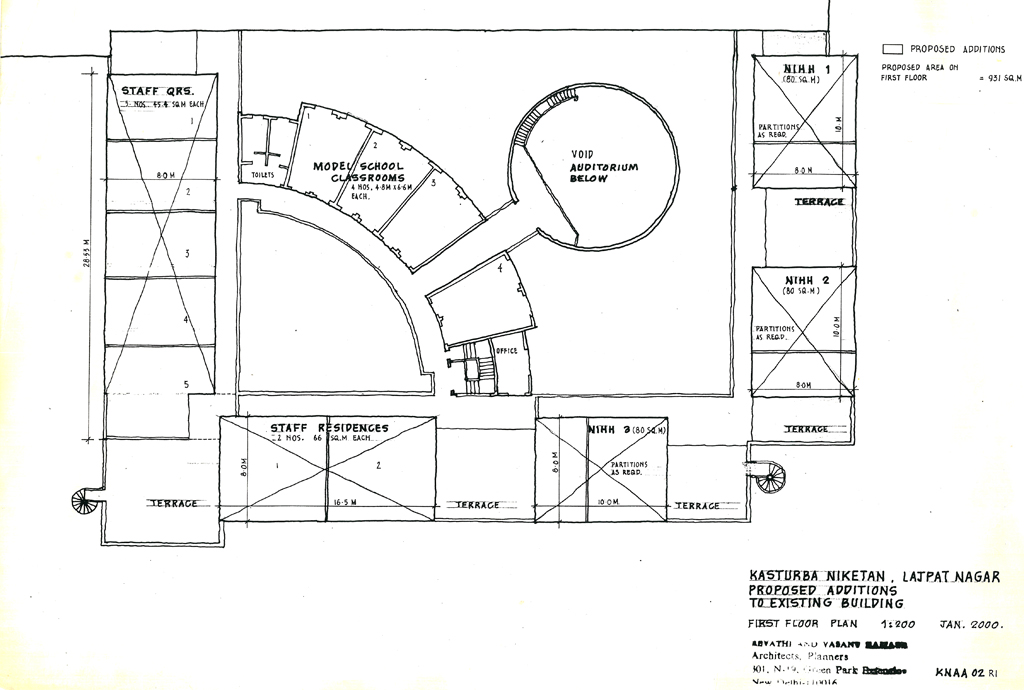

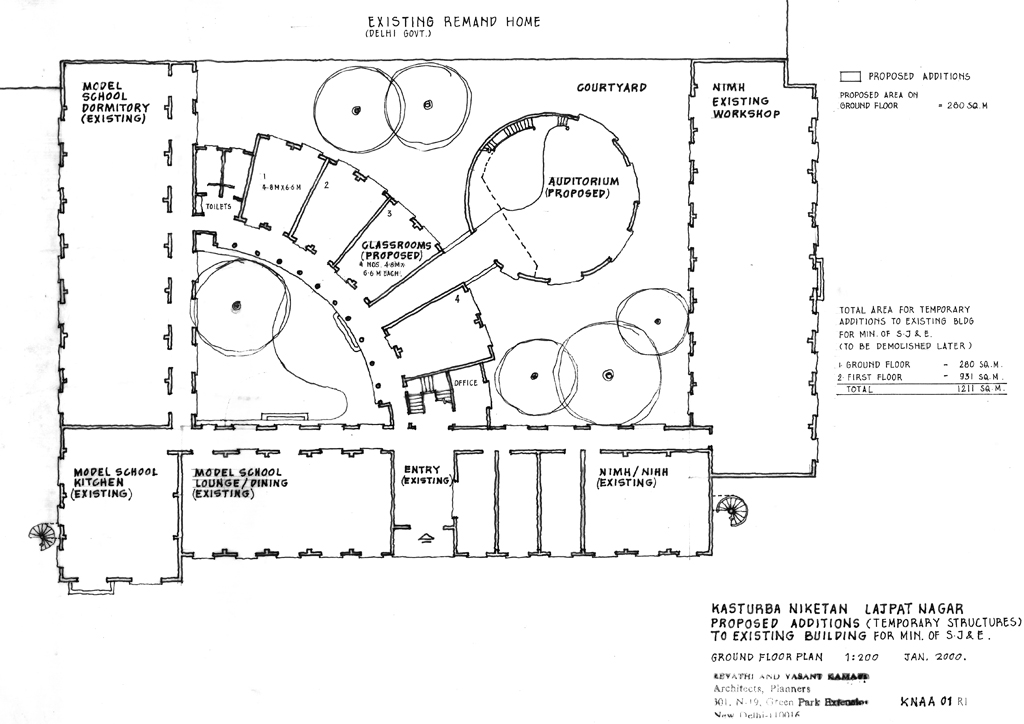

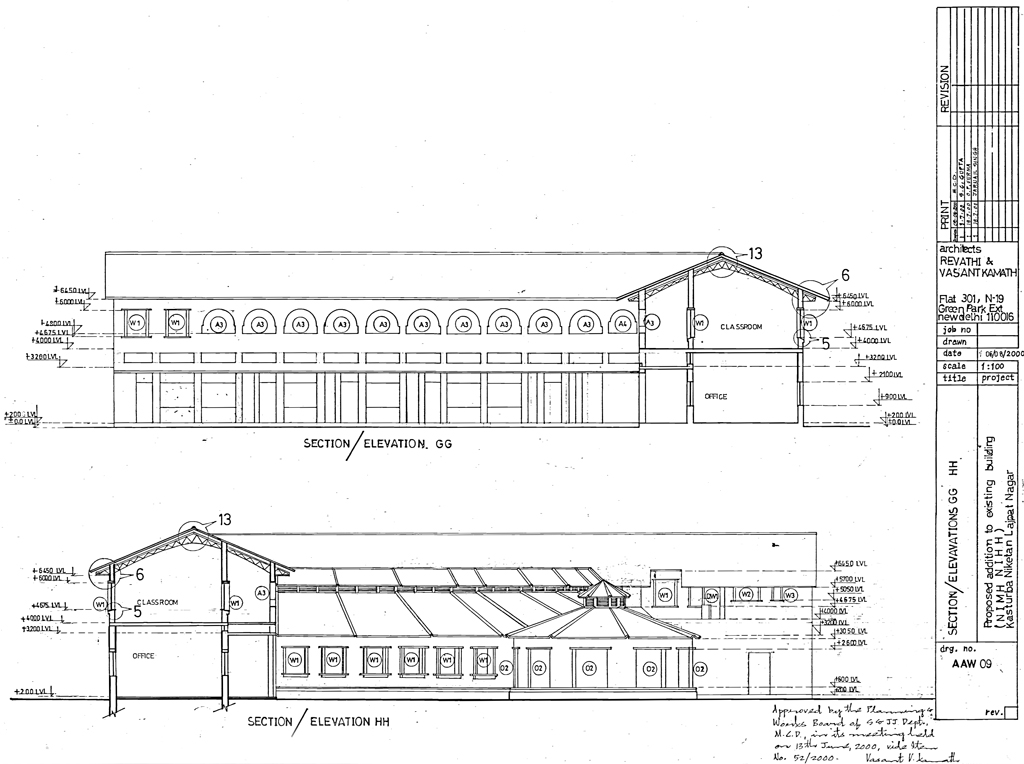

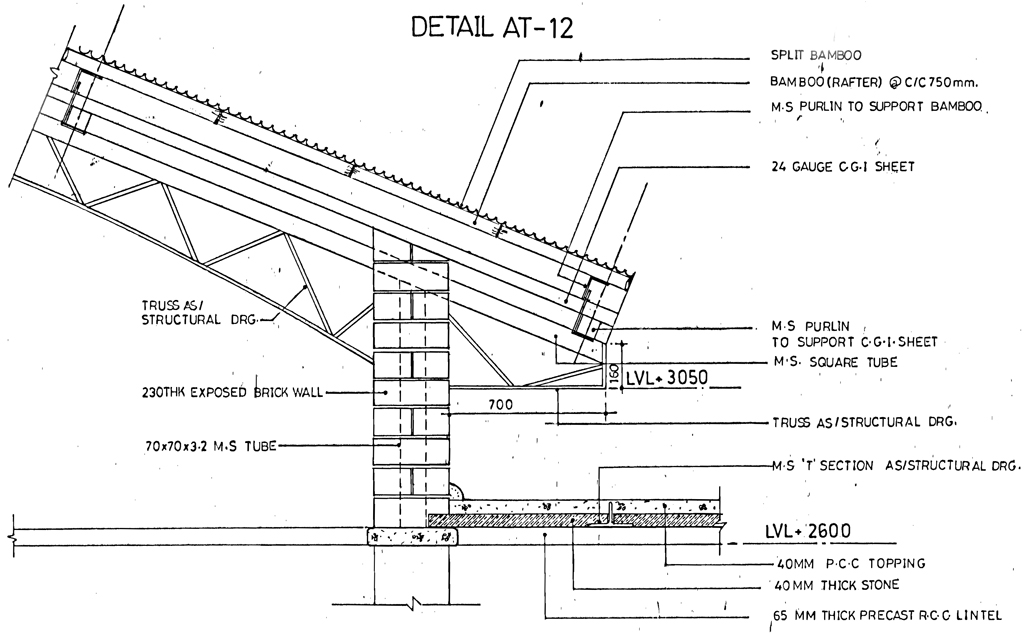

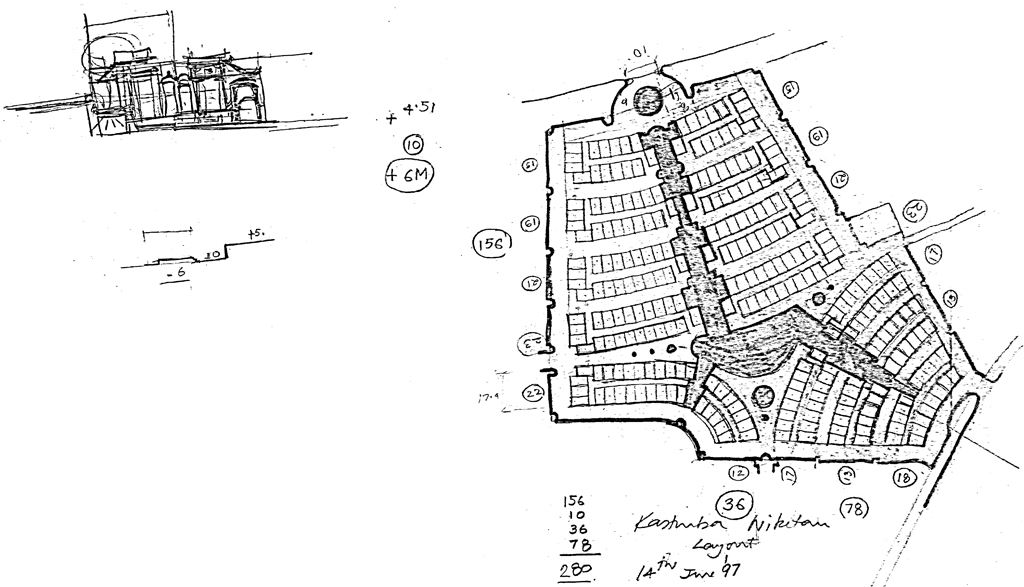

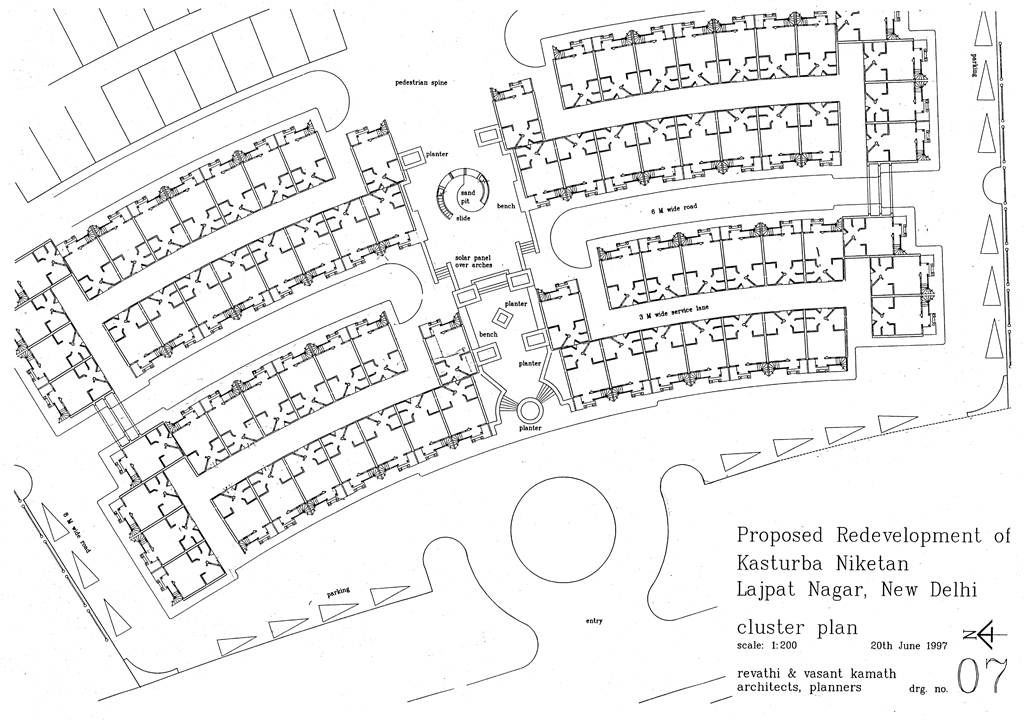

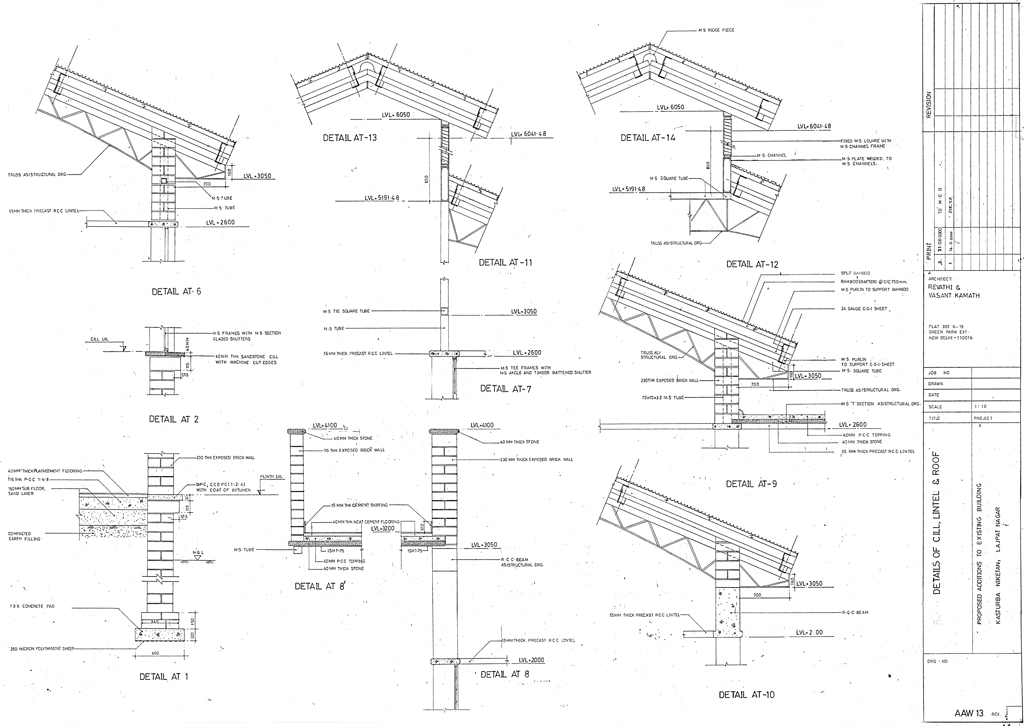

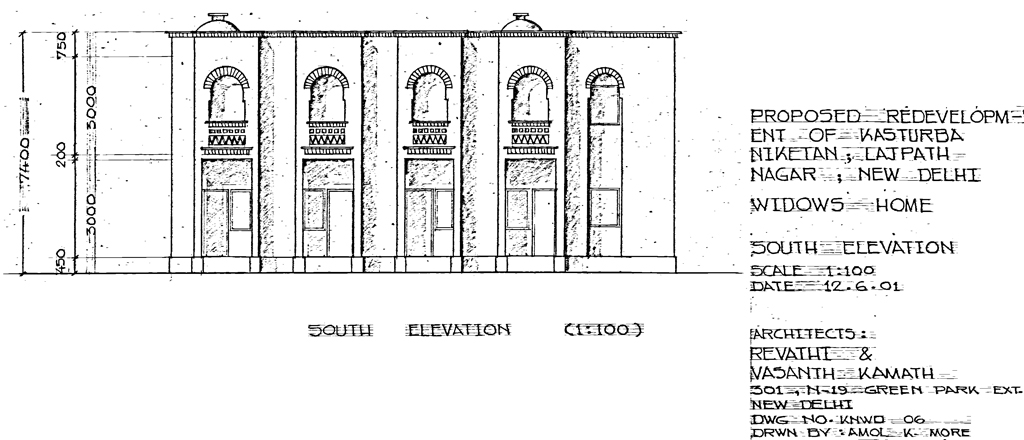

In the first phase, government institutions scattered on the land were provisionally consolidated in a single area by adding space on top of and around the main existing government buildings. The three hectares of land thereby freed were developed into a sites-and-services project to house the 285 refugee families.

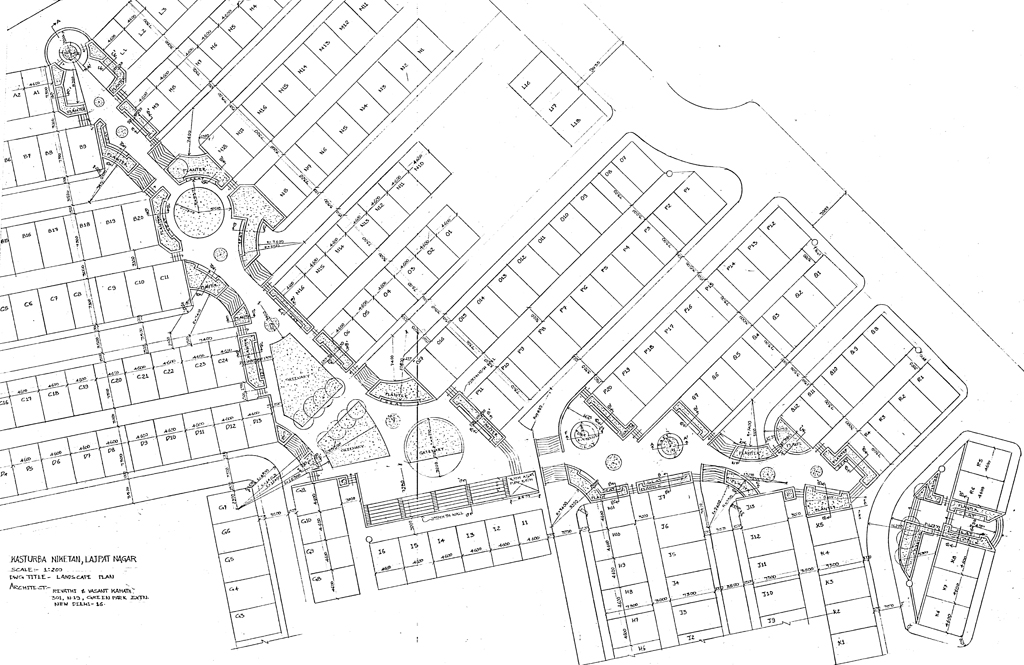

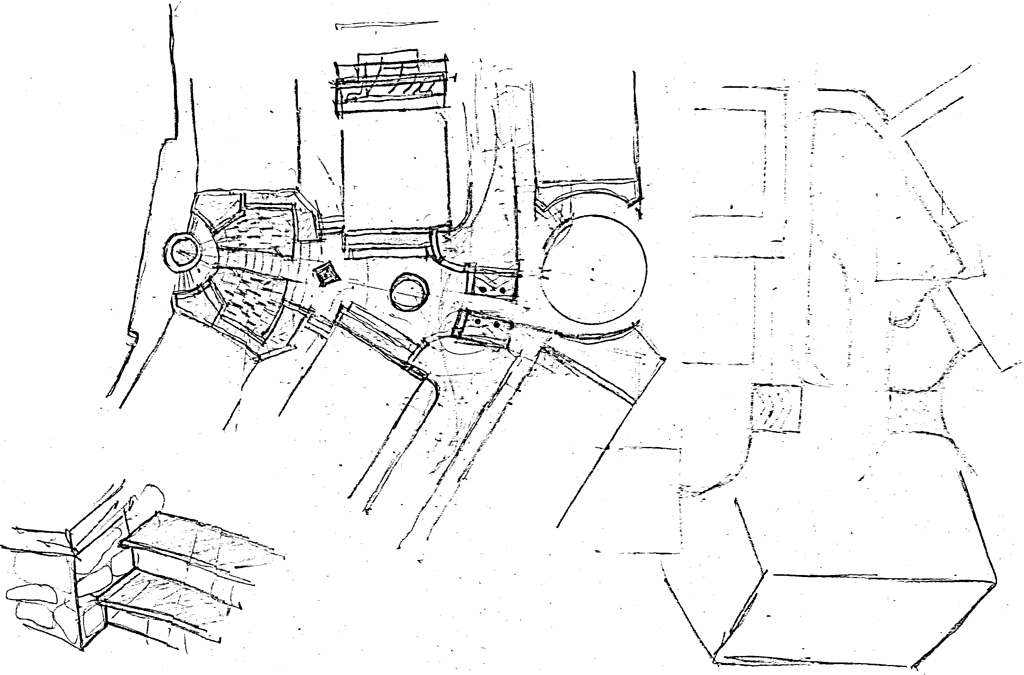

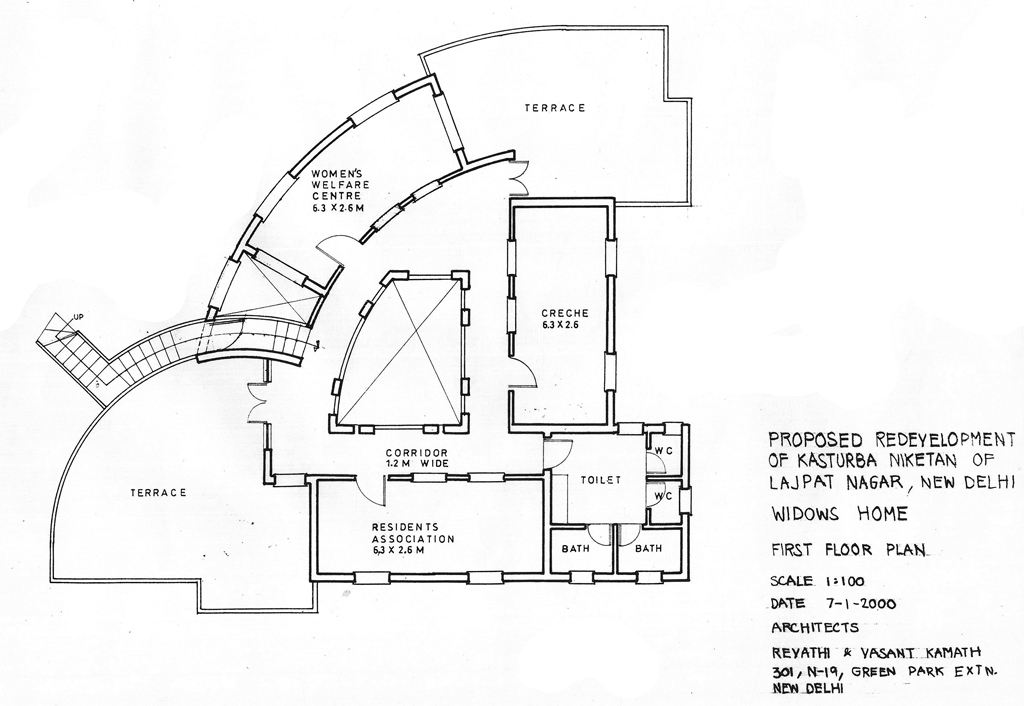

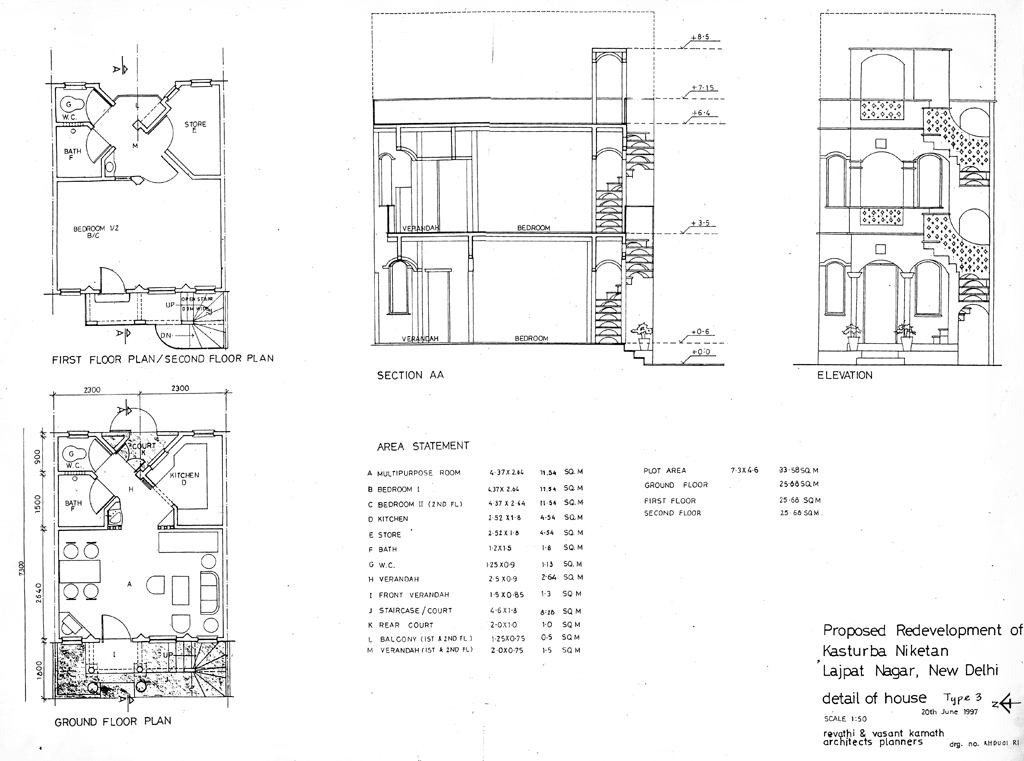

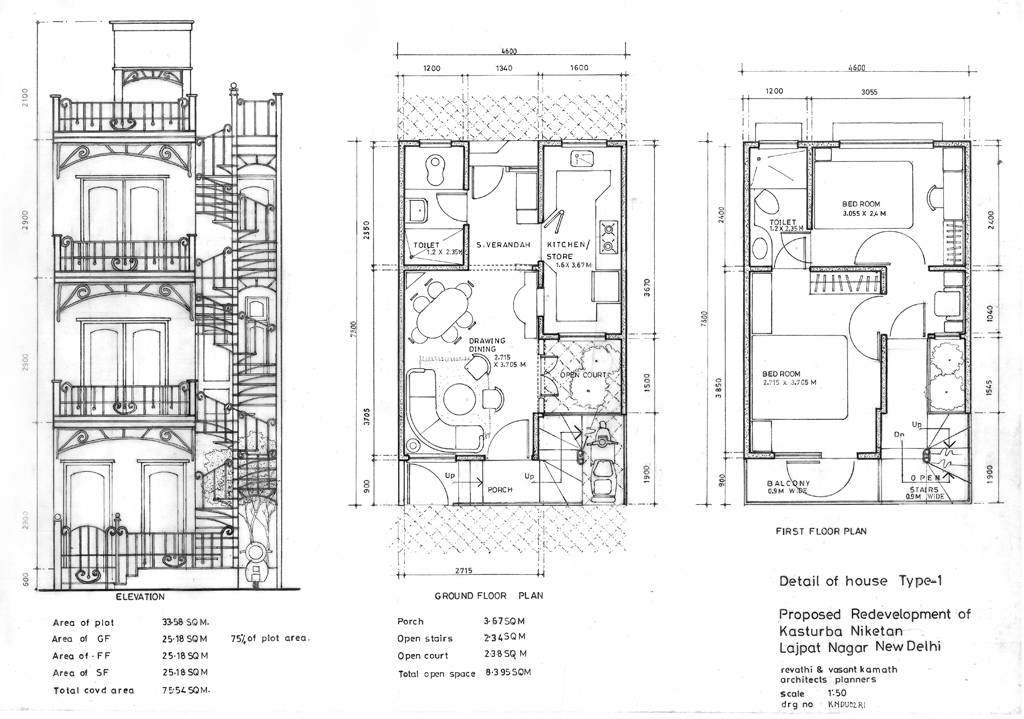

Initially, each family was to be alloted a plot of 36 sqm in conformity with slum resettlement colony plots of Delhi. However, this plan was opposed by the families, as they did not want to be equated with slum redevelopment schemes. The protests resulted in a change to a participatory design model in consultation with the residents association. The new design resulting from this process had 40 sqm plots with service lanes between them for light and cross-ventilation (unlike slum redevelopment schemes with back-to-back plots).This scheme also included a green pedestrian spine running through the plots, a park, and a community centre. To gain approval for construction, three prototype house plans were developed to cater to the differing needs of the residents.

Once approved, the plots of land were allotted to the refugee families to build houses on these plots. Today, however, the government institutions continue in their provisional spaces while the land allocated for their permanent sites lies unused with squatters. The community facilities envisaged in the design were also left undeveloped by the concerned municipal departments and remain in administrative limbo.